A lot of the work we do as archivists revolves around the nuts and bolts of keeping a collection of historically significant documents safe and easily accessible for the researchers who need access to that information. Making sure that the humidity and temperature in the storage room are kept within safe limits, checking for insect damage or mould, or the main task in Whitby Museum Archives at the moment of creating a structured and easily accessible catalogue of the collection – describing what we have in a standardised format that shows the links between each item, etc.

Every now and then, however, you’ll find a few items that – when you take them together – tell a story.

Every now and then we get to put the cataloguing on pause for a moment and do a little detective work.

In the 1830’s Whitby was starting to see a decline from its earlier success. The main industries of the town – whaling and shipbuilding – had been slowly dropping off for years. Jet jewellery was starting to pick up as a formal sign of mourning. The Whitby-Pickering railway (initially built for horse-drawn vehicles) was opening in stages bringing tourists into the town.

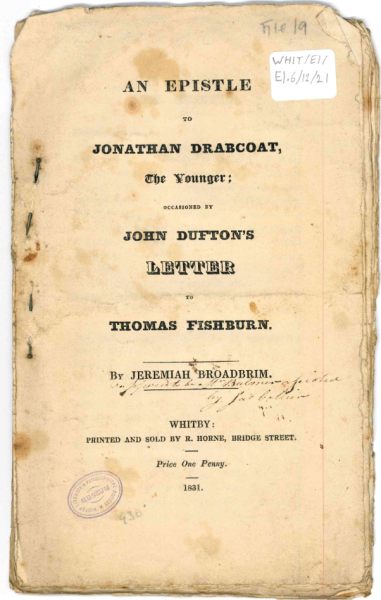

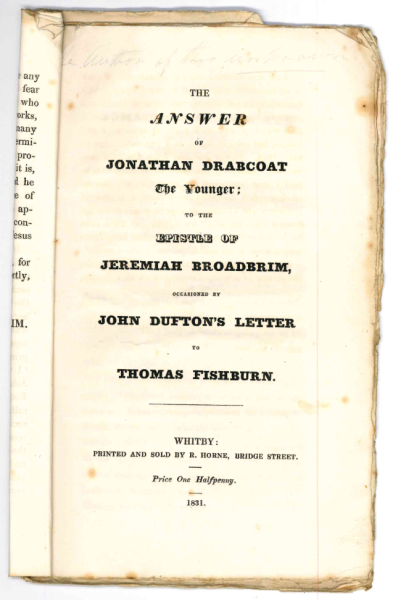

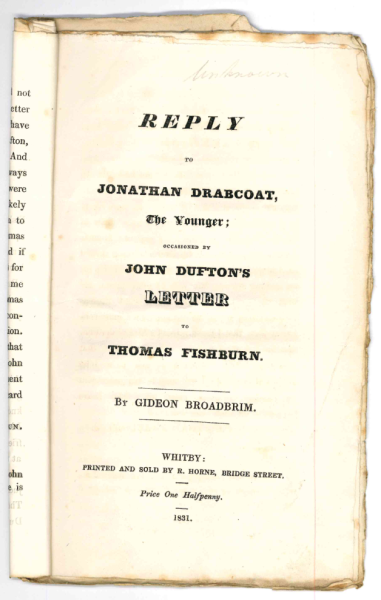

During all of this the people of Whitby would often publish their work on their hobbies or letters and correspondence they thought were significant to the public as limited run pamphlets – printed and sold by R Horne (printer, book-seller, ship owner and eventual founder of the Whitby Gazette) – for public consumption. Almost like an earlier analogue form of modern social media.

One such collection of pamphlets and booklets that we’ve found in the collection recently tells us at least part of a story that must have been a major topic of conversation and discussion in Whitby at the time.

In ‘An Epistle to Jonathan Drabcoat the Younger, Occasioned by John Dufton’s Letter to Thomas Fishburn’ Jeremiah Broadbrim criticises the words, actions, and thoughts of John Dufton and Thomas Fishburn. Jeremiah argues that they both show ‘unchristian pride’, and concludes that John Dufton specifically needs to show more humility in his work.

Then we find Gideon Broadbrim, Jeremiah’s brother, entering the conversation with ‘A Reply to Jonathan Drabcoat the Younger; occasioned by John Dufton’s Letter to Thomas Fishburn’. Here he explains that he has been researching John’s claimed past as a teacher and minister and has found no evidence of any sort of veracity. He ends by comparing John Dufton to the sort of character you might expect to find ‘in some profane play’.

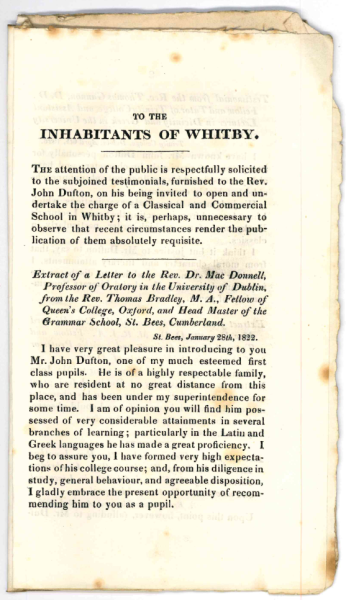

John Dufton defends himself at the end of the collection though, with a booklet published under the title ‘To the Inhabitants of Whitby’. Here he explains that he is perfectly suited to opening a school in Whitby dedicated to teaching Commerce and The Classics; and includes a list of testimonials from academics in the University of Dublin, Trinity College, and from priests at St George’s and St Thomas’s churches in Liverpool. He ends the booklet with a statement asserting the credibility of those character references, and noting how happy he is to be setting up a school in Whitby for education in Commerce and the Classics.

While this is just a collection four small pamphlets, not even 20 pages in total, you can still see the story they tell.

From what we can tell from those pamphlets in the early 1830’s John Dufton came to Whitby with the intention of establishing a new school in Whitby. Before he could get that started though, he picked a fight with a man called Thomas Fishburn (a well-known and respected ship-builder in Whitby at the time), apparently over religious matters. This fight must have been public, vocal, and unpleasant enough to upset Thomas Fishburn’s friends that they started looking into who this John Dufton actually was, after all nobody they could talk to had ever heard of him before.

While this investigation was happening the argument between Dufton and Fishburn appears to have continued, possibly getting unpleasant enough to make John Dufton worry about it affecting his plans to open a school in Whitby, leading to him publishing a booklet full of (alleged) testimonials from respectable academic and religious leaders, all describing what a wonderful man he is.

It is strange though, that the only one of the men giving their character references can be verified today – Richard Mac Donnell, although it is strange that a man who was still in his first year of a BA course would be an official tutor at the University of Dublin. This would suggest that we would need to be a little sceptical about the credibility of the testimonials.

Considering that we can’t find any record of John Dufton’s school ever being opened or progressing past the planning stage (where it was when his argument with Thomas Fishburn started) it seems that the people of Whitby in 1831 were also somewhat sceptical of his claims and credentials.

By Charles Graffius (Archive Manager)

#HeritageFund #archivesforall

If you are interested in viewing this archive document, contact [email protected] The document location is WHIT/E1/E1.6/12/21 (Green Box 19 Local Government).