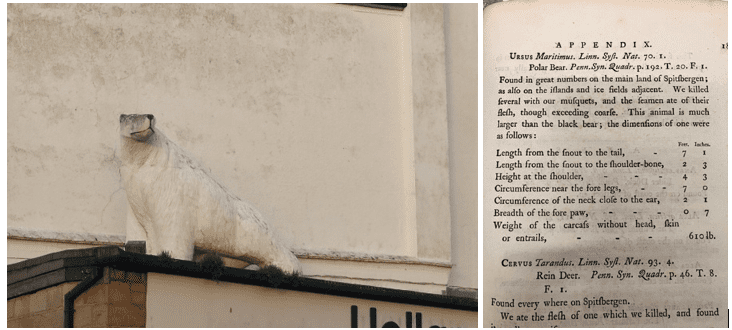

If you stand facing the east side of Whitby’s swing bridge, you may spot a large white bear hiding atop a shop roof, gazing over the River Esk. Whilst locals and regular visitors pass it by without a second thought, newcomers and holidaymakers spot it almost instantly, often wondering: Why is there a statue of a polar bear in Whitby?

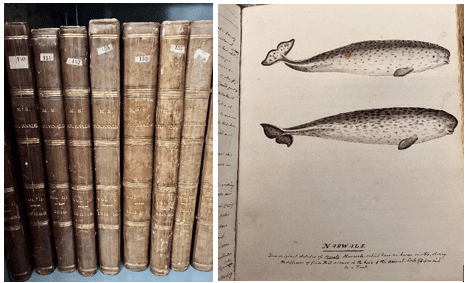

To uncover the truth behind this odd statue, we must dive into Whitby’s history with polar bears. Although the species had been well-known in Britain for hundreds of years, the first formal scientific description of a polar bear was written by the Whitby-born Lord Mulgrave, Constantine John Phipps, in 1773. [1] Phipps’ North Polar expedition, which included a young Horatio Nelson and Olaudah Equiano, regularly encountered bears.

Whilst Captain Cook, who apprenticed in Whitby, never reported seeing living polar bears whilst exploring the Arctic, they were encountered by the crew of his third voyage following his death in Hawaii. [2]

Although online sources state that live polar bears were regularly transported to Whitby, there’s little evidence supporting this claim. The transportation of live polar bears to Whitby is poorly documented and is only described in a handful of accounts. In one of these few accounts, Robert Burbank Holt asserts that his father, John Holt (born 1797), kept a polar bear at his ropery and sail-loft at Spital Bridge. The bear was ‘occasionally indulged with a swim, when friends were assembled to witness the performance’. [4]

One particular example of a living bear is usually linked to the statue, brought back to Whitby by the Arctic whaler William Scoresby Senior (1760-1829). Some websites claim that the bear was kept at Scoresby’s home on Church Street. Others claim it was chained up next to the swing bridge and swam in the River Esk. [5] On Facebook, some people have claimed that Scoresby walked the bear down Flowergate and Golden Lion Bank on a chain. Others argue that the bear was kept in a garden on Grape Lane. These claims often fail to document the source of the polar bear story and never verify the alleged connection between the statue and Scoresby Senior’s bear.

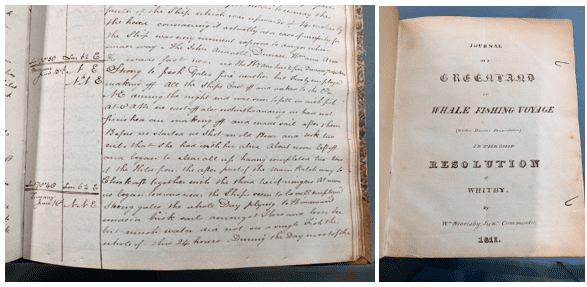

Before examining whether Scoresby’s bear inspired Whitby’s statue, we will first uncover the truth of Scoresby’s polar bear story by returning to its source. The only account of Scoresby Senior’s polar bear was published in 1851, written by his son, the Arctic whaler, explorer and scientist William Scoresby Junior (1789-1857). In a memoir of his father, Junior notes that ‘On one occasion, when a female bear with cubs had been attacked, one of the young ones was taken alive. It was a fine, and, for a cub, well-grown animal.’ [6] Although Junior didn’t document when the polar bear cub was taken, an entry in his father’s whaling log-book for June 2nd 1796 notes ‘(…) at meridian killed a she bear & one pup & took the other pup alive- which is rather decertified [sic] with his fresh lodgings’, which likely refers to the same animal. [7] Senior had the cub secured the deck with a rope, which ‘very unexpectedly made a spring at him, but fortunately, checked by his rope, failed in the ferocious intent’. Following the cub’s attempted attack, Senior set about taming it by physically chastising it each time it lunged at him. Within two or three days, Senior had tamed the cub. [8]

Senior’s log-book indicates that he and his bear cub arrived in Whitby on June 27th 1796. [9] Junior notes that the cub, nicknamed ‘Bruin’ (an English folk term for bears), was moved to an oil yard, where ‘blubber was landed, in order to [be] reduced into marketable oil’. [10] This oil yard was a blubber rendering works built for and owned by Henry Walker Yeoman (1749-1800), located on the east bank of the River Esk (near the site of Larpool Viaduct). [11] Word quickly spread about Bruin, who ‘the inhabitants of Whitby flocked out in masses to see’. Somehow, the bear cub escaped into Larpool Wood, which adjoined Yeoman’s oil yard. Junior writes that ‘Men and lads, assisted by dogs, and armed with guns and a variety of other destructive weapons, were speedily in progress, and with overwhelming superiority, towards the retreat of the bear, with a view to its destruction’. [12] Luckily for Bruin, Scoresby Senior was alerted to the escape and made his way to Larpool Wood. He found the bear cub surrounded by a crowd preparing to attack it. Junior writes that, to the crowd’s amazement, Senior walked up to Bruin and ‘patted the shaggy neck, as he placed a prepared noose of the rope around it, and then quietly led away the furious brute, which, under his commanding guidance, became as tractable as a lap-dog!’. [13]

After Bruin’s escape, it became clear to Scoresby Senior that taking care of an increasingly large and agitated polar bear cub would be, in his son’s words, an ‘inconvenience’. Junior notes that whilst his father could’ve earned a considerable sum by putting the cub on show around the country, he decided that it should go to the Tower of London menagerie, where it could be better cared for. [14] This menagerie, established in the early 1200s by King John, was initially used to house exotic animals donated to the English monarch, but by the 18th century acted as a repository for all manner of exotic animals brought to Britain. One of the earliest animals housed at the menagerie was a polar bear (donated to Henry III by the King of Norway in 1252), which reportedly swam in the Thames and hunted for fish. [15] Centuries later, from approximately 1787-1792, the Tower of London housed a Canadian polar bear, donated by a ‘Colonel Clanoe’, erroneously described as the ‘first of its colour in England’. [16]

Scoresby Senior arranged for Bruin to be donated to the Tower of London menagerie and sent him to London in a coaster. [17] Catalogues of animals in the menagerie, published in regular editions of the Tower guidebook ‘An Historical Description of the Tower of London, and its curiosities’, suggest that the Tower of London received a ‘fine young Greenland bear, of considerable size’ in late 1796. [18] This ‘fine young bear’ is mentioned again in the 1799 edition, and in 1800 is described as ‘very large; this species grow to the size of an ox’. In editions from 1804, 1805, 1806 and 1809, the bear was instead described as a ‘large Greenland bear’. [19] These guidebook entries likely all refer to Scoresby’s bear, with the ‘large Greenland bear’ an updated description of the now-grown ‘fine young bear’, but they may describe two different animals.

In summary, Bruin likely arrived in Whitby in late June 1796, escaping from Yeoman’s oil yard within a matter of weeks. He was then transported to the Tower of London before the end of the year, where he grew from a ‘fine young bear’ to a ‘large Greenland bear’. He lived in the menagerie until he died in 1809. [20]

Scoresby Junior notes that his father met Bruin again about a year after he was sent to London. The following is an account of their final meeting, reproduced in full. The keeper referred to, may be George Payne, who was keeper of the menagerie from 1775-1800, or one of his under-keepers, whose names have sadly been lost to history. [21]

‘It was about a twelvemonth or more, I believe, after Bruin’s regular installation among the wild beasts of the National collection, that my Father, happening to be in London, determined on taking a look at his old acquaintance, Bruin. Proceeding to the Tower, he paid the usual entrance fee, and without intimating anything about his special object, took the course through the collection, like other visitors, as guided by the exhibitor. His eye being wistfully directed in advance of his position, he at length got sight of the looked-for object; when, breaking away from those pursuing the prescribed progress, he hurried directly up to where his ursine friend was encaged. A warning cry came urgently from the keeper, who had noticed his near and bold approach to a place of danger- “Take care, sir, that is one of the most ferocious animals in the collection”, but it was disregarded. My Father only paused, whilst, by his familiar and accustomed salutation,-“Poor Bruin! poor fellow!”-he gained the attention of the animal, when, catching its eye, and perceiving he was recognised, he went quietly up, thrust his arm through the cage, and, whilst he patted the neck and head of the evidently delighted creature, received a species of fawning response, which was eloquently interesting and touching. The keeper, who had rushed forward on witnessing the daring intrusion on the interior of the bear’s cage, now stood fixed in almost speechless astonishment. At length, lifting his hands with a characteristic indication of his extreme amazement, he exclaimed, “Why, sir, I never saw the like of that all the days of my life!”’ [22]

Considering this information, it is possible to dismiss some of the claims made online about Scoresby’s bear. Bruin wasn’t kept next to the swing bridge; he lived in Yeoman’s oil yard, on the east side of the River Esk. As he lived on the East side of Whitby, about a mile from the town, it is highly unlikely that he visited Scoresby’s house on Church Street, nor any gardens on Grape Lane, nor is it likely that he walked down Flowergate or Golden Lion Bank. Bruin may have swum in the River Esk, but Scoresby Junior never recorded this, and this detail is likely taken from Robert Burbank Holt’s account of his father’s polar bear on Spital Bridge. The claim that Scoresby’s bear swam in the Esk may even be a misremembering of stories of the Tower of London’s first polar bear swimming in the Thames.

Before examining whether Bruin was the inspiration for Whitby’s polar bear statue, it may be of some interest to note that Scoresby Junior also transported a living polar bear cub to Whitby. In the June 15th entry of Junior’s whaling journal for 1812, he notes that he ‘shot an old bear and took two cubs that she had with her alive.’ The following day, Junior wrote that ‘The two bears we took yesterday seem pretty contented, one of them walks around at large and is quite harmless, the other somewhat larger and not quite so inoffensive.’[23]

To determine the origins of Whitby’s polar bear statue and whether it commemorates Scoresby Senior’s bear, we must examine issues of the Whitby Gazette, accessible in the Whitby Museum Library. The statue is first mentioned on July 27th 2001, in an article titled “City link spells a still brighter town Christmas”. This article reports that the Whitby Christmas Lights Committee had recently acquired several new displays from a group affiliated with Leeds Council, including ‘spectacular pieces like a big polar bear’. [28] The bear was installed and lit up on a pontoon in the lower harbour for Christmas 2001, and again the following Christmas. [29] When the polar bear failed to make an appearance in Christmas 2003, his absence was noted in an article titled “Where’s the polar bear?”. The article explains that, due to the electricity cable needed to light up the bear, Scarborough Borough Council was unable to accept the public liability responsibility of placing it on a pontoon again. [30]

‘Pictured with the Polar Bear are Saul Black and Graham Palmer, of the lights committee’, 2001, photo: Alan Wastell [31]

Following public outrage, it was decided that the polar bear would be installed for Christmas 2004. In response to the good news, the Whitby Gazette announced a competition to name the bear statue. [32] As placing the statue on the pontoon was deemed a health and safety risk, it was instead installed on the rooftop of a shop near the swing bridge. [33] On January 7th 2005, the Whitby Gazette announced that Amber Newton, aged 5, had won their competition and had named the bear ‘Snow Prince’. [34]

‘Snow Prince’ being installed on a rooftop near the harbour for the first time, November 2004, photo: Alan Wastell [35]

Every year from 2005 to 2010, Snow Prince was installed back on his rooftop for Christmas, then removed again in January. However, in 2011, Snow Prince was installed for the last time after the warehouse where he was usually stored closed down. [36] With nowhere left to store him, the decision was made to leave him atop his rooftop.

His once bright white coat has faded in the summer sun, and moss has given him a slight tinge, but he now stands as one of Whitby’s most recognisable, and possibly one of its strangest, landmarks. As fewer and fewer people realise that the statue overlooking the harbour was originally nothing more than a festive decoration, Whitby’s polar bear has become more and more of a local legend. It’s not clear exactly how or when Snow Prince was associated with Scoresby’s bear. Perhaps the statue’s strangeness encouraged people to reach into Whitby’s whaling history to find an explanation for its existence, or possibly people just want an excuse to talk about one of the quirkier episodes from Whitby’s past.

Although it’s clear that he bares no historical connection to Whitby’s polar bears, he acts as a welcome commemoration of them. After all, Snow Prince stands gazing at the same River Esk that Captain Scoresby’s Bruin did during his time in Yeoman’s oil yard, over two centuries ago. Regardless of its origins, Whitby’s polar bear statue serves as an unusual, yet memorable, reminder of a time when Whitby was a gateway to the unforgiving Arctic, connecting the town’s present with its adventurous maritime past.

By special request we can arrange for individuals to access the Scoresby Archive and material relating to the Whitby polar bears- please email [email protected]

The research carried out when writing this article was made possible by the resources of the Whitby Museum Library and Archive. If you would like to read the full account of Scoresby Senior’s bear, visit us and ask to see pages 78 to 86 of My Father by William Scoresby Junior. If you would like to read more about Snow Prince, visit the Whitby Museum Library to access the Digital Whitby Gazette. The Library also possesses copies of other books used to write this article, including: The Arctic Whaling Journals of William Scoresby the Younger, Vol 1, edited by Colin Ian Jackson; Whitby Past and Present by Robert Burbank Holt; Whitby Lore and Legend by Percy Shaw Jeffery; and Alan Appleton’s Whitby Timeline (see references for relevant page numbers).

By Eddie Jenkins BA History (Aberystwyth University) & MA Museum Studies (University of Leicester) (volunteer)

#archivesforall

I would like to express my gratitude to Emma Shepley at Historic Royal Palaces, Malcolm Mercer at Royal Armouries, Fiona Barnard, Phil Richards and my fellow volunteers at Whitby Museum Library & Archives for all their assistance.

References

[1] Phipps, Constantine John, A voyage towards the North Pole: undertaken by His Majesty’s command, 1773, (London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols, 1774), p.185.

[2] Cook, James, Journal of Captain Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific Ocean, on discovery; performed in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, (London: E. Newbery, 1781), p.352.

[3] Jeffery, Percy Shaw, Whitby Lore and Legend, Third Edition (Whitby: Horne & Son, 1952, p.140.

[4] Holt, Robert Burbank, Whitby Past and Present, (Whitby: Messrs Horne & Son, 1897), p.13.

[5] Atlas Obscura, ‘Scoresby’s Polar Bear’, online, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/scoresbys-polar-bear; Real Yorkshire Blog ‘Ever wondered why is there a Polar Bear sitting above Holland & Barrett near the bridge in Whitby?’, online, https://www.realyorkshireblog.com/post/ever-wondered-why-is-there-a-polar-bear-sitting-above-holland-barrett-near-the-bridge-in-whitby

[6] Scoresby Junior, William, Memorials of the Sea: My Father: Being Records of the Adventurous Life of the Late William Scoresby, (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851), p.79.

[7] Scoresby Senior, William, ‘Journal for 1796’ in Seven Log-Books concerning the Arctic Voyages of Captain William Scoresby, Senior of Whitby, England Vol. 2, (New York: Explorer’s Club, 1916), p.25.

[8] Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, pp.79-80.

[9] Scoresby Senior, ‘Journal for 1796’, p.34.

[10] Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, p.81.

[11] Appleton, Alan, The Whitby Timeline, Third Edition, (Whitby: Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, 2022), pp.103-104.

[12] Junior refers instead to ‘Cock-mill wood’, a woodland adjoining the south of Larpool Wood. As Larpool Wood adjoined Yeoman’s oil yard, it seems more likely that the polar bear cub escaped into Larpool Wood, and Junior used ‘Cock-Mill wood’ as a term for both woodlands.

[13] Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, pp.81-82.

[14]Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, p.82.

[15] Historic Royal Palaces, ‘The Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London’, online, https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/history-and-stories/the-tower-of-london-menagerie/

[16] An Historical Description of the Tower of London, and its curiosities (London: 1787), p.25; An Historical Description (1789), p.25; An Historical Description (1792), p.25.

[17]Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, p.83.

[18] An Historical Description (1796), p.17.

[19] An Historical Description (1799), p.17; An Historical Description (1800), p.17; An Historical Description (1804), p.15; An Historical Description (1805), p.15; An Historical Description (1806), p.15; An Historical Description (1809), p.15.

[20] An article published in Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany on 19th September 1812 claims that the last polar bear in the Tower of London menagerie died ‘about four years ago’, suggesting that the ‘large Greenland bear’ died in late 1808 or early 1809.

[21] Grigson, Caroline, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp.172-173.

[22] Scoresby Junior, Memorials of the Sea: My Father, pp.83-84.

[23] Scoresby Junior, William, ‘Journal for 1812’, in The Arctic Whaling Journals of William Scoresby the Younger, vol. I: The Voyages of 1811, 1812 and 1813, edited by Colin Ian Jackson, (London: Hakluyt Society, 2003), p.102.

[24] Scoresby Junior, ‘Journal for 1812’, p.109.

[25] Scoresby Junior, ‘Journal for 1812’, p.125; ‘Monthly Memoranda in Natural History- Polar Bear’, The Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany Volume 74: 1812-09, pp.652-653.

[26] Jameson, Robert, ‘Letter to William Scoresby 05/12/1812’, WHITM:SCO567.5.

[27] Jameson, Robert, ‘Letter to William Scoresby 16/10/1814’, WHITM:SCO567.7b.

[28] Holmes, Damian, ‘City link spells a still brighter town Christmas’, Whitby Gazette 27/07/2001, p.15.

[29] ‘Bearing up in spotlight’, Whitby Gazette 27/11/2001, p.1; ‘Festive display is bear-ing up well in the harbour’, Whitby Gazette 17/12/2002, p.14.

[30] ‘Where’s the polar bear?’, Whitby Gazette 12/12/2003, p.1.

[31]‘Bearing up in spotlight’, Whitby Gazette 27/11/2001, p.1.

[32] Levy, Marie, ‘Polar Bear will return to help light up town’, Whitby Gazette 22/10/2004, p.3.

[33] ‘Christmas crowds ready for big switch on of festive lights tonight’, Whitby Gazette 26/11/2004, p.3.

[34] Levy, Marie, ‘The day Amber met her prince…’, Whitby Gazette 07/01/2005, p.11.

[35] ‘Christmas crowds ready for big switch on of festive lights tonight’, Whitby Gazette 26/11/2004, p.3.

[36] ‘Hunt for place to store town’s festive lights’, Whitby Gazette 18/11/2011, p.9.